Introduction to Walk Like a Sloth: lessons in ground sloth locomotion

Getting Oriented

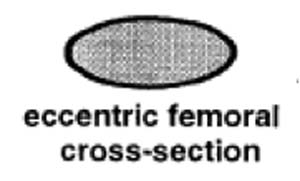

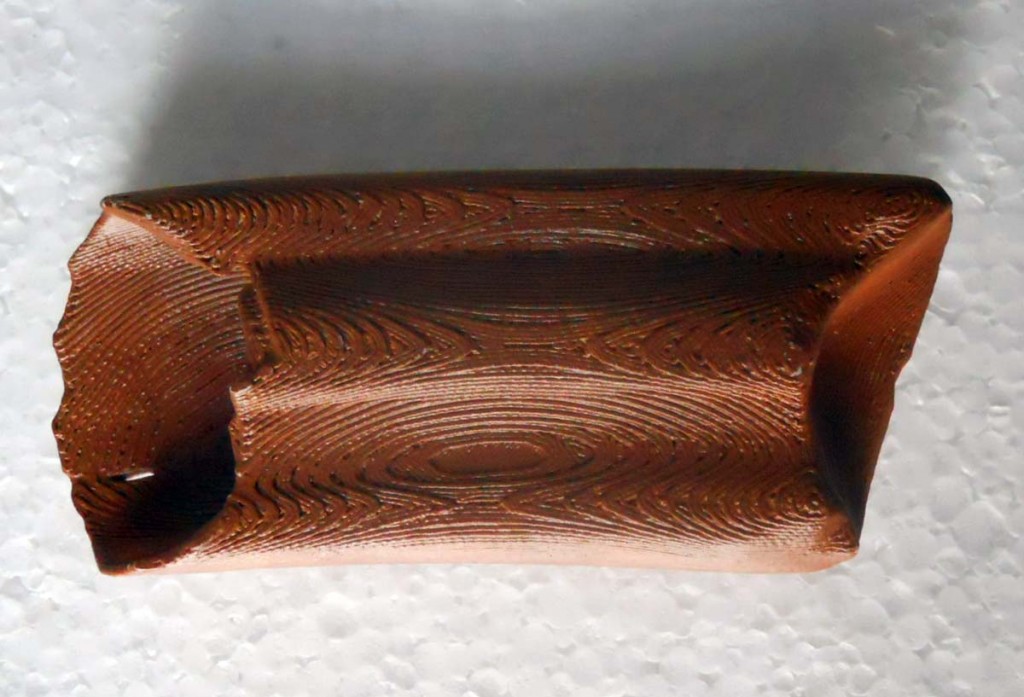

The femur or thigh bone is the largest bone in the sloth’s body and one of the most unusual bones of any animal owing to to its tremendous width and eccentric cross-section.  The round head fits into a cup-shaped socket in the pelvis or hip called the acetabulum, while the far or distal end forms the knee joint, articulating with both the tibia or shin bone and patella or knee cap. The head of the femur points upward, about 35° below vertical, and angles forward about 45°, matching the backward-pointing hip sock. This gives Megalonyx a unique knees-wide-apart stance. (McDonald, 1977) The distal (down) end of the bone has a shallow wide depression in the center of one side–that’s the trochlea or patellar groove, where the patella articulates. That’s anterior (forward) obviously, so this femur came from the sloth’s left leg.

The round head fits into a cup-shaped socket in the pelvis or hip called the acetabulum, while the far or distal end forms the knee joint, articulating with both the tibia or shin bone and patella or knee cap. The head of the femur points upward, about 35° below vertical, and angles forward about 45°, matching the backward-pointing hip sock. This gives Megalonyx a unique knees-wide-apart stance. (McDonald, 1977) The distal (down) end of the bone has a shallow wide depression in the center of one side–that’s the trochlea or patellar groove, where the patella articulates. That’s anterior (forward) obviously, so this femur came from the sloth’s left leg.

Getting Oriented

Getting Oriented Look closer

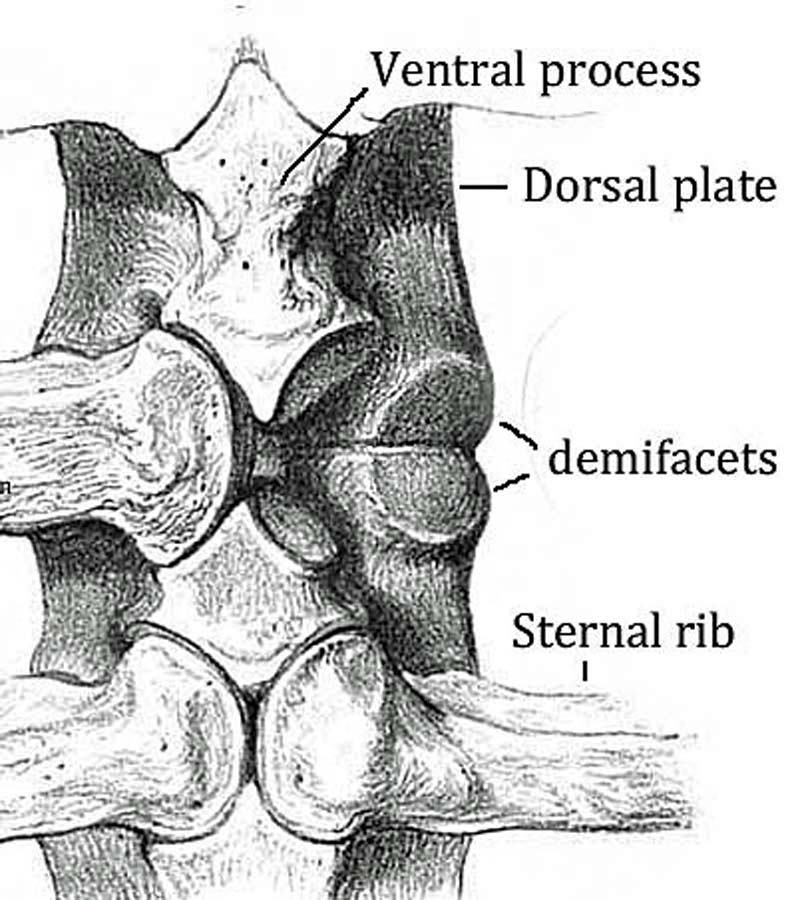

Look closer magnifying the arm’s power. The smoother, flatter side is the ventral or “in” side, configured to fit snugly against the ribs on the back. The scapular

magnifying the arm’s power. The smoother, flatter side is the ventral or “in” side, configured to fit snugly against the ribs on the back. The scapular

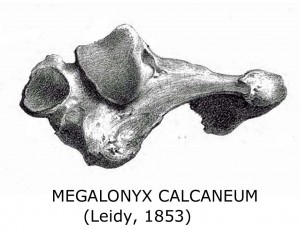

The astragalus has a convex side (the superior or “up” side) and concave (inferior or “down”) side. With the convex side up you’ll see a heart-shaped articulating surface—orient the bone so it looks like a Valentine’s Day heart. The smooth surface on the left side of the heart wraps around the bone and makes a right angle down to the bottom. The

The astragalus has a convex side (the superior or “up” side) and concave (inferior or “down”) side. With the convex side up you’ll see a heart-shaped articulating surface—orient the bone so it looks like a Valentine’s Day heart. The smooth surface on the left side of the heart wraps around the bone and makes a right angle down to the bottom. The