If predators killed the sloths, and the site hasn’t been disturbed too much (e.g. by scavengers, trampling, weathering, transport, etc.), the killers’ fingerprints will still be present. The signs of predation versus mere scavenging, according to Haynes, are in the evidence left behind after the meal—the kind of damage to specific bones, the pattern of disarticulation, and the arrangement of the bones around the kill site (Haynes, 1980a). Different predators have different MO’s. Those vary with the specific prey species, the season, environmental conditions, how hungry the predators are, how much meat is available, and how many individuals there are in the pack or pride (Haynes, 1983). The patterns are so regular that one can reliably look for causes other than predation when deviations from the norm are observed.

The Ice Ages offered a formidable cast of killers, but attacking a healthy adult Megalonyx, (a.k.a. “Giant Claw”) wasn’t a job for a solitary predator. Downing a giant sloth demanded teamwork. The giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) was once thought the greatest terror on four legs and maybe capable of going it alone, but modern studies suggest its size owed more to its herbivorous habits and bone-crushing/scavenging abilities, and at best it was only an opportunistic predator (Emslie and Czaplewski, 1985). The number of sabertooth cats (Smilodon fatalis) found at La Brea with serious wounds suggests a social structure that made it possible for them to survive even crippling injuries, but whether that cooperation extended to hunting is TBD. Evidence from Friesenhahn Cave in Texas indicates it was used as a den by the more lightly-built sabertooth, Homotherium serum, the scimitar cat. All the living Felids that den are solitary, however (Rawn-Schatzinger, 1992). The remains in the cave suggest H. serum specialized in racing in under the noses of momma mammoths and dispatching careless two year-olds with a strategic bite or two, and then dashing away apparently to wait for the youngster to bleed to death and the herd to depart, no doubt in frustrated fury. Other Homotherium species in the Old World followed similar practices with juvenile mastodons and rhinos (Lange, 2002). Bits of Harlan’s sloth (Paramylodon harlani) have been recovered from Friesenhahn Cave but there’s no evidence a cat brought it there, much less killed it (Graham, 2007). The scimitar cat’s style of hunting makes it a solid candidate for causing the wound we’ve found on our toddler’s back, but it would not have tried the same trick on an adult sloth. American lions (Panthera leo atrox) probably hunted like their African cousins, by stealth and ambush around watering holes and other locations frequented by their prey (Grayson, 1991). The absence of any fossils from eastern North America suggests, like their modern descendents, they preferred open habitat to the woodlands favored by Megalonyx (McDonald and Anderson, 1991). The lifestyle of dire wolves (Canis dirus) is still debated, but their massive teeth suggest scavenging probably played the preeminent role in their diet. If predators killed our sloths, the prime suspect has to be a social hunter like the timber wolf (Canis lupus). That’s lucky, because Gary Haynes has spent a lifetime studying wolf kill sites.

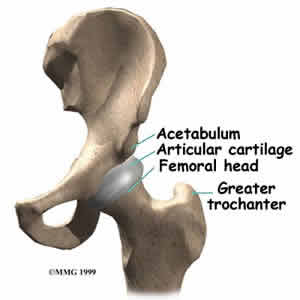

Every predator has a unique approach to eating a specific prey species and even when they leave no distinctive tooth marks (which is the rule), they often leave a telling signature in the specific areas they damage bones, the elements they ignore and the arrangement of the carcass when they leave. When wolves prey on moose and bison the most reliable indicator is the damage to the femora (Haynes, 1980b). Even with very light feeding, wolves destroy the greater trochanter. Now the greater trochanter of any prey species is hardly a tasty tidbit–wolves that attack here have one purpose—cutting the muscles that hold the bone in the acetabulum or hip socket. Predators are dangerous–to other animals and sometimes to each other. Even social predators can turn decidedly asocial in the blood lust of a kill—they demand elbow room. The first principle for recognizing the kill site of a social predator likethe timber wolf is looking for the evidence of the divvying up the spoils and creating the needed separation.

Next week—a look at our sloth femur: Dancing with wolves . . . . Dave

Next week—a look at our sloth femur: Dancing with wolves . . . . Dave

References

Graham, RW. 2007. Stratigraphy and paleontology of Friesenhahn Cave, Bexar County, Texas. Society of Vertebrate paleontology, 67th Annual Meeting, October 15-16, 2007. Field Trip Guidebook: 27-45.

Grayson, DK. 1991. Late Pleistocene mammalian extinctions in North America: taxonomy, chronology, and explanations. Journal of World Prehistory 5: 193-231.

Haynes G. 1980a. Prey bones and predators: potential information from analysis of bone sites. Ossa: 7: 75-97.

Haynes, G. 1980b. Evidence of carnivore gnawing on Pleistocene and recent mammalian bones. Paleobiology 6: 341-351.

Haynes, G. 1983. A guide for differentiating mammalian canivore taxa responsible for gnaw damage to herbivore limb bones. Paleobiology 9: 164-172.

Lange, IM. 2002. Ice age mammals of North America: A guide to the big, the hairy, and the bizarre. Mountain Press Publishing Company. Missoula, Montana.

McDonald, HG and Anderson, DC. 1983. A well-preserved ground sloth (Megalonyx) cranium from Turin, Monona County, Iowa. Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 90: 134-140.

Rawn-Schatzinger, V. 1992. The scimitar cat Homotherium serum Cope. Illinois State Museum Reports of Investigations 47: 1-80.

Are there any maps from the Tarkio Valley site of the bone arrangement that might show a pattern of disarticulation?

3 sloths going down at once still sounds like a lot of predators to me. My vote is for drowning in a flooded creek or some other natural catastrophe.

Just watched something on National Geographic that showed how seemingly healthy bison in Yellowstone were being taken out in small groups by toxic gasses released from thermal vents. Nothing like that in Pleistocene Iowa was there?

Hi Pete,

No geothermal activity like that in Iowa that I’ve ever heard of. Meghann is still working on the bone distribution map. Haynes says he has seen wolves take down a juvenile with an adult moose and bison. Our problem is explaining why TWO juveniles, a year or more apart in age, were hanging around. (Could the wound in the back of the toddler have slowed its development?) A natural catastrophe usually leaves the bones of other animals–we don’t have anything but sloths. I’m rethinking drowning too, but a flood is out–it would have carried in and dropped gravel and rocks equal to the density of the sloths. The clay the bones are buried in indicates little or no water velocity. How do you like the idea of falling through ice and drowning in a lake or the backwaters of a river in the winter?

Falling through ice sounds good. Mama trying to help struggling young one – baby goes in with her. Or possibly mom goes through and kids follow her in blindly – could open up some interesting ideas in the sloth behavior department.

Has there been any pollen analysis or other clues from the sediment samples that might point to the time of year they died?

We have a preliminary pollen and seed report but that’s going to give us too wide of a snapshot–we can’t say they were deposited at the time of death. Forensic scientists use insects to estimate TOD, but of course they’re dealing with maggots and flesh. They have largely ignored aquatic insects, unless they are on floating carcasses. I’m curious about aquatic insects and crustaceans that might use defleshed bones for a substrate for laying eggs. Also some species of ostracodes lay eggs and molt in a particular season. . . hide inside a skull maybe? . . . Art Bettis here has a student doing a preliminary survey of microfossils–we’ll decide what we want to examine closer based on his report.

There isn’t an absence of lion fossils east of the Mississippi. The very first Pantera leo atrox specimen was found in Natchez, Mississippi. A very large lion skull has been recovered in Florida, and some fossil specimens of lions have been recovered in South Carolina.

Thanks for the correction Mark. I should have said they were rare in the East, not totally absent. Faunmap is a wonderful resource but I guess it has it limits. I’m wondering if the Florida record could strengthen the case for the lions preferring open habitat. I’m thinking about Florida also serving as a refuge for Nothrotheriops shastensis, another westerner otherwise.

(see http://www.museum.state.il.us/research/faunmap/)

The presence of Nothroptheriops shastensis in Florida is possible but not likely. Unlike most other eastern sites, Florida’s Pleistocene fossil record is relatively complete and so far I don’t believe any specimens of that species have been found in state. However, specimens of prairie chickens, magpies, and thirteen-lined ground squirrels have been found in Georgia and Florida, so there was some open habitat with Western species. There’s also that disjunct population of burrowing owls.

Mark, your’re right about Nothrotheriops being limited to the mountainous West in the Rancholabrean, but Akersten and McDonald (1991) suggest the genus may have been more widespread in the Irvington. It’s reported from the central Florida Pool Branch (McDonald, 1985) and Leisey Pit 1A (Webb et al., 1989). Their theory is that the sloth’s low body temperature didn’t limit its distribution so long as North American climate stayed relatively stable, but the wider swings associated with the late Pleistocene limited the animal’s range to regions where it could find shelter to moderate the extremes (e.g. in caves) or migrate vertically relatively easily (e.g. up and down mountains).

References

Akersten, W.A. and McDonald, H.G. 1991. Nothrotheriops from the Pleistocene of Oklahoma and Paleogeography of the genus. The Southwestern Naturalist 36: 178-185.

McDonald, H.G. 1985. The Shasta ground sloth Nothrotheriops shastensis (Xenarthra, Megatheridae) in the Middle Pleistocene of Florida. In The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths and Vermilinguas, G.G. Montgomery (ed.) pp. 95-104.

Webb, S.D., Morgan, G.S., Hulbert, R.C., MacFadden, B.J. and Mueller, P.A. 1989. Geochronology of a rich early Pleistocene vertebrate fauna, Leisey Shell Pit, Tampa Bay, Florida. Quaternary Research 32: 96-110.