It doesn’t sparkle like the Hope diamond or King Tut’s gold, but the most amazing artifact in the museum is an oblong softball-sized coprolite from a ground sloth. It came to us from a donor who in the early 1970’s helped her father, a National Park Service ranger, collect samples from a cave near the west end of the Grand Canyon. Kids being kids, a couple of the giant horse apples were ”forgotten” on the bottom of a knapsack—puny wages for a day of packing sloth poop down to an NPS boat 500 feet below, on a path scuffed out by very different feet 30,000 years earlier. The donor lives in Iowa now and read about the sloth project. . . the rest you know.

It doesn’t sparkle like the Hope diamond or King Tut’s gold, but the most amazing artifact in the museum is an oblong softball-sized coprolite from a ground sloth. It came to us from a donor who in the early 1970’s helped her father, a National Park Service ranger, collect samples from a cave near the west end of the Grand Canyon. Kids being kids, a couple of the giant horse apples were ”forgotten” on the bottom of a knapsack—puny wages for a day of packing sloth poop down to an NPS boat 500 feet below, on a path scuffed out by very different feet 30,000 years earlier. The donor lives in Iowa now and read about the sloth project. . . the rest you know.

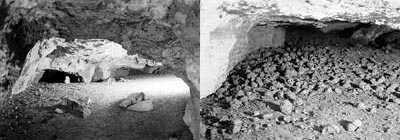

Like the ruins of a medieval cathedral, Rampart Cave today only hints of its former glory. It once held the largest deposit of ground sloth dung known. But in 1976 a careless hiker left a campfire smoldering inside the cave and the deposit was almost entirely consumed—a tragedy Paul Martin has likened to loss of the ancient library at Alexandria, Egypt (Martin, 2005). Bones from the cave indicate the dung belongs to the Shasta sloth, Nothrotheriops shastensis, the smallest of the four North American late-Pleistocene ground sloths. Like Megalonyx they became extinct at the end of the ice ages 12,000-odd years ago. The identification was recently confirmed in a major breakthrough in DNA sequencing (Poinar et al., 1998). Some researchers from that same team are trying to repeat their accomplishment with our bones now. (images below borrowed from http://www.geocities.com/shioshya/paleo/index.htm)

The dung ball smells sweet, like incense, with no lingering odor of ammonia or feces. I had the notion of getting a scratch-and-sniff souvenir made for the museum gift shop and pursued getting the smell reproduced. I contacted a couple of companies that offered an impressive selection of synthetic scents. They promised to get back to me, but never did. Too bad, they could have been a big hit with the kids.

The dung ball smells sweet, like incense, with no lingering odor of ammonia or feces. I had the notion of getting a scratch-and-sniff souvenir made for the museum gift shop and pursued getting the smell reproduced. I contacted a couple of companies that offered an impressive selection of synthetic scents. They promised to get back to me, but never did. Too bad, they could have been a big hit with the kids.

Experts have found over 70 different species of plants in the Rampart deposits. Many occur in just trace amounts—probably ingested accidentally while the animals browsed. The bulk of the Shasta diet apparently consisted of desert globe mallow (Sphaeralcea laca), Mormon tea (Ephedra navadensis), saltbush (Atriplex), reed grass (Phragmites), acacia (Acacia greggii), yucca and agave. A UI botany student looked at that list and explained the problem reproducing the smell—the plants aren’t especially aromatic . Scratch-and-sniff works best with sharp distinctive scents, not the subtle bouquet of French wine.

People and sloths apparently like to eat the same kinds of things, especially around a salad bar. Admittedly, Megalonyx may have had an entirely different diet than Shasta–no one has ever found a deposit of their dung to know for sure. But we do have a preliminary report on the pollen from the site, which allows us to describe a sloth forest generally and make some judgments about the food that would have available. It’s the kind of forest Native Americans preferred too, and long labored to maintain–and that may not be a coincidence. One might speculate about the role sloths and other ice age megafauna had in creating this forest before people, and the degree to which they eased the way for humans to replace them and spread across the continent. (image borrowed from http://www.artlex.com/ArtLex/Reh.html)

People and sloths apparently like to eat the same kinds of things, especially around a salad bar. Admittedly, Megalonyx may have had an entirely different diet than Shasta–no one has ever found a deposit of their dung to know for sure. But we do have a preliminary report on the pollen from the site, which allows us to describe a sloth forest generally and make some judgments about the food that would have available. It’s the kind of forest Native Americans preferred too, and long labored to maintain–and that may not be a coincidence. One might speculate about the role sloths and other ice age megafauna had in creating this forest before people, and the degree to which they eased the way for humans to replace them and spread across the continent. (image borrowed from http://www.artlex.com/ArtLex/Reh.html)

Details about the pollen and the Iowa sloth forests in 2 weeks.. . . Dave

Martin, P.S. 2005. Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age extinctions and the rewilding of America. University of California Press. Berkley, CA.

Poinar, H.N., Hofreiter, M., Spaulding, W.G., Martin, P.S., Stankiewicz, B.A., Bland, H., Evershed, R.P., Possnert, G., Paabo, S. 1998. Molecular coproscopy: dung and diet of the extinct ground sloth. Science 281: 402-407.

My favorite bit of info relating to all the Shasta dung balls is that the analyses show Nothrotheriops to be a bit of a nomad that wandered around and ate pretty much whatever plant matter it came in contact with.

Supposedly there are some dung balls for Mylodon darwini from South America but I don’t believe there have been any studies of content as in depth as those for Nothrotheriops. A pity as it would be nice to compare the diets, even if they are from two widely separated sloths, both taxonomically and geographically.

Hi Rob–Eating everything and anything was long my impression too, to tell you the truth. I’ve been searching for the source of that (mis)information and haven’t found it yet. Hanson (1978) identified the remains of 72 different genera in the 500-odd poop-balls he analyzed from Rampart Cave, but the plants I cited in my post represent 90% of what he found. I also recollect seeing a plant list somewhere that included some species indigestible to most other mammals, but Hanson says Shasta’s tastes were pretty tame and comparable to other large mammals, i.e. they ate what was available and there’s no sign they found a special niche eating the ugly stuff. He suggests that lacking front teeth they couldn’t be picky eaters and accidentally ingested some of the plants on his list while they were gathering mouthfuls of the favored species. Poinar et al. (1998) sequenced the DNA in poop from Gypsum Cave and found some of the same things, and nothing that conflicts with Hansen’s conclusions. He added capers and mustard to the list of common plants, suggesting they were so easily digested that perhaps nothing survived to be recognizeable by Hanson’s macroscopic technique. The bottomline remains—this is a sloth that would have enjoyed any salad bar in town–especially the all-you-can-eat kind.

Hanson, R.M. 1978. Shasta ground sloth food habits, Rampart Cave, Arizona. Paleobiology 4: 302-319.

Poinar, H.N., Hofreiter M., Spaulding, W.G., Martin, P.S., Stankiewicz, B.A., Bland, H., Evershed, R.P., Possnert, G., and Paabo, S. 1998. Molecular coproscopy: dung and diet of the extinct ground sloth Northrotheriops shastensis. Science 281: 402-406.

Rob–I found the source of my confusion about Shasta’s diet. Martin et al. (1961) looked at the pollen alone in the dung and found some things that most other herbivores shun (e.g. creosote bush and cactus). They concluded that Shasta occupied a unique niche that no other North American animal filled before or since. They discuss the possibility of the pollen coming from non-dietary plants landing on the leaves of ingested plants and confounding the results, but apparently it was a bigger factor than they assumed. I’m kind of pleased about the change in view. This sloth business wouldn’t be half so interesting if their success could be explained as easily as their occupying a unique diet niche.

Reference: Martin P.S., Sabels, B.E. and Shutler, D. Jr. 1961. Rampart cave coprolite and ecology of the Shasta ground sloth. American Journal of Science 259: 102-127.