Cedar Rapids has released its plan for restoring the neighborhoods ravaged by this summer’s floods. I’m disappointed. I was hoping for a bolder vision, something that recognized the increased likelihood of future floods and turned the riverfront in a more sustainable direction—like an Ice Age Zoological Park recreating the sloths’ habitat. Besides serving as an important tool for education and research about Iowa’s truly natural environment (i.e. before Native American alterations to the land) and a valuable wildlife corridor, a natural environment park would bring significant commercial development opportunities, tourist revenue and jobs. A riverfront park could be designed to meet the Cedar River half way and work with its perennial floods instead of against them, like the truce Davenport, IA has forged with the Mississippi. Restored wetlands, lakes and other containment basins could absorb water rather than speeding its way onward to create bigger problems for the communities downstream. Large urban zoological parks aren’t without precedent. The 1,800-acre San Diego Zoo Wild Animal Park is one of the largest tourist attractions in southern California with attendance of 2 million visitors annually (Wikipedia, 2008). Why not here? (image One Way Street by bpkelsey, borrowed from)

Cedar Rapids has released its plan for restoring the neighborhoods ravaged by this summer’s floods. I’m disappointed. I was hoping for a bolder vision, something that recognized the increased likelihood of future floods and turned the riverfront in a more sustainable direction—like an Ice Age Zoological Park recreating the sloths’ habitat. Besides serving as an important tool for education and research about Iowa’s truly natural environment (i.e. before Native American alterations to the land) and a valuable wildlife corridor, a natural environment park would bring significant commercial development opportunities, tourist revenue and jobs. A riverfront park could be designed to meet the Cedar River half way and work with its perennial floods instead of against them, like the truce Davenport, IA has forged with the Mississippi. Restored wetlands, lakes and other containment basins could absorb water rather than speeding its way onward to create bigger problems for the communities downstream. Large urban zoological parks aren’t without precedent. The 1,800-acre San Diego Zoo Wild Animal Park is one of the largest tourist attractions in southern California with attendance of 2 million visitors annually (Wikipedia, 2008). Why not here? (image One Way Street by bpkelsey, borrowed from)

The preeminent role the extinct Pleistocene megafauna played in shaping the North American landscape has largely gone unrecognized here despite abundant corroborating evidence from across the ocean. The megamammals in Africa (i.e. animals > 1 ton, e.g. elephants, rhinos, hippos and large giraffes) play a keystone role in managing their habitats (Owen-Smith, 1988). Elephants especially are constantly transforming the landscape. By debarking and toppling large trees they create habitat for other animals, and open the forest floor to sunshine allowing a variety of other plants to flourish. The flush of new growth paves the way for smaller animals to multiply. Elephants and hippos create trails and dig wallows and water holes, providing the edges, corridors and microhabitats for fugitive species to settle in and the resources they need to survive. By transporting the fruit and seeds of select plants large mammals further encourage the diversity of the forest. Mastodons, mammoths and ground sloths played a similar sweeping role in Ice Age North America (Soulé and Noss, 1998).

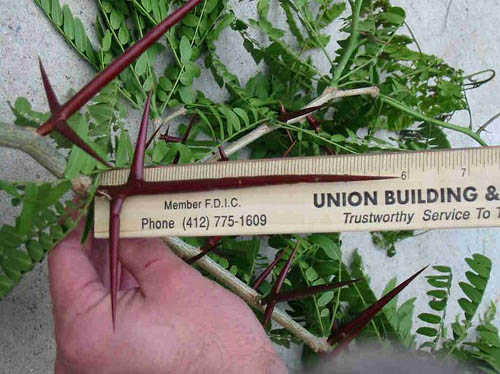

The loss of the Pleistocene mega-mammals has left us with a number of plants strangely ill-adapted to modern times, with seeds and fruits too large to be swallowed or transported and largely ignored by animals today (e.g. Osage Orange, right), or with profligate defenses that seem obvious over-kill with respect to

The loss of the Pleistocene mega-mammals has left us with a number of plants strangely ill-adapted to modern times, with seeds and fruits too large to be swallowed or transported and largely ignored by animals today (e.g. Osage Orange, right), or with profligate defenses that seem obvious over-kill with respect to  contemporary threats (e.g. Honeylocust, left). These characteristics only make sense when one considers the vanished herbivores with whom these plants evolved, and which disappeared just an evolutionary eye-blink ago. Barlow (2000) calls these dispossessed plants ice age ghosts and orphans.

contemporary threats (e.g. Honeylocust, left). These characteristics only make sense when one considers the vanished herbivores with whom these plants evolved, and which disappeared just an evolutionary eye-blink ago. Barlow (2000) calls these dispossessed plants ice age ghosts and orphans.

Insects, birds and small mammals were affected as well –pronghorns, for example, have evolved to run 60 mph, but no North American predator can approach that speed. A perplexing misallocation of biological resources by evolution until one considers the extinction of the North American cheetah, which presumably could run only 59 mph (Byers, 1997). We are surrounded by these ice age reminders or “shadows,” and some very familiar species are facing serious challenges today now that the activities of the temporary stand-ins for the keystone megafauna, Native Americans, have been curtailed (e.g. burning). (image borrowed from)

Insects, birds and small mammals were affected as well –pronghorns, for example, have evolved to run 60 mph, but no North American predator can approach that speed. A perplexing misallocation of biological resources by evolution until one considers the extinction of the North American cheetah, which presumably could run only 59 mph (Byers, 1997). We are surrounded by these ice age reminders or “shadows,” and some very familiar species are facing serious challenges today now that the activities of the temporary stand-ins for the keystone megafauna, Native Americans, have been curtailed (e.g. burning). (image borrowed from)

The problem of disjointed ecosystems is particularly acute on the Great Plains where, bereft of native browsers and much to the consternation of its ranchers, the landscape is becoming overgrown with shrubs inedible to the favored species–cattle–non-natives, of course. Scientists have proposed “rewilding” the region with surrogates for the missing megafauna from Africa and Asia (Donlan et al. (2006). Proponents admit a tremendous amount of research needs to be completed before a horde of nonnative species is unleashed into the environment (Martin, 2005).

A rewilding experiment is progress now in Siberia. Zimov is seeking to transform over 60 square miles of Arctic tundra to grasslands by establishing breeding populations of Alaskan musk oxen, Siberian ponies and Canadian woodland bison (Stone, 2001). He believes the grazing, trampling, and manure of the large animals will eventually result in the replacement of the tundra mosses by the short subarctic grasses, a community that vanished with the mammoths 12, 000 years ago (Guthrie, 1990). Several less formal experiments are going on here in the United States with the protection of wild horses and burros on public lands in the West and the reintroduction of condors in the Grand Canyon, but no one has tried an experiment exploring the impact of mega-browsers on the Eastern woodlands .

Rewilding Iowa isn’t in the cards—the land is simply too valuable for farming. Furthermore, the space available in the Cedar Rapids plan isn’t enough to accommodate large animals in sustainable numbers or the natural disturbance regime of the river, much less the landscape transformation power of megafauna like elephants,  but a park could be expanded considerably beyond the downtown limits through a combination of purchase, long-term leases and conservation of easements on connecting riverfront up and downstream. In the face of an accute shortage of mastodons, Zimov plans to use bulldozers to mimic the ice age disturbance regime. We might try black rhinos, giraffes and John Deeres. As Einstein once said, “If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be called research, would it?” (Haynes, 2004). A Cedar Rapids park would be uniquely positioned, sitting at the junction of three state universities with their considerable agricultural, biological and engineering research expertise. (photo by Phil Douglis, borrowed from)

but a park could be expanded considerably beyond the downtown limits through a combination of purchase, long-term leases and conservation of easements on connecting riverfront up and downstream. In the face of an accute shortage of mastodons, Zimov plans to use bulldozers to mimic the ice age disturbance regime. We might try black rhinos, giraffes and John Deeres. As Einstein once said, “If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be called research, would it?” (Haynes, 2004). A Cedar Rapids park would be uniquely positioned, sitting at the junction of three state universities with their considerable agricultural, biological and engineering research expertise. (photo by Phil Douglis, borrowed from)

Is an Ice Age Sloth Park possible? Can we even begin to guess what Iowa’s forests looked like when the sloths were alive, or is an Ice Age Park just a fantasy like the late unlamented Coralville rainforest? Yes, it’s possible, and we don’t have to guess. We have preliminary reports back on the seeds and pollen from the site. They may provide a compelling picture of Iowa and the land the sloths called home. More about the seeds and pollen next week. . . . Dave

References

Barlow, C. The Ghosts of Evolution: Nonsensical fruit, missing partners, and other ecological anachronisms. Basic Books. New York, NY.

Byers, J. 1997. American Pronghorn: Social adaptations and the ghosts of predators past. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, IL.

Donlan, C.J., Berger, J., Bock, C.E., Burney, D.A., Estes, J.A., Foreman, D., Martin, P.S.,, Roemer, G.W., Smith, F.A., Soule, M.E., and Greene, H.W. 2006. Pleistocene Rewilding: An optimistic agenda for twenty-first century conservation. The American Naturalist 168: 660-681.

Guthrie, RD. 1990. Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The story of Blue Babe. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, IL.

Haynes, G. 2004. Rather odd detective stories: a view of some actualistic and taphonomic trends in paleoindian studies. Breathing Life into Fossils: Taphonomic Studies in Honor of C.K. (Bob) Brain. T. Pickering, K. Schick, and N. Toth (eds.) Stone Age Institute Press. Gosport, IN.

Martin, P.S. 2005. Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age extinctions and the rewilding of America. University of California Press. Berkley, CA.

Owen-Smith, R.N. 1988. Megaherbivores: The influence of very large body size on ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Soulé, M. and Noss, R. 1998. Rewilding and biodiversity: complementary goals for continental conservation. Wild Earth Fall, 1998: 18-28.

Stone, R. 2001. Mammoth: resurrection of an ice age giant. Perseus Publishing. Cambridge, MA.

Dave, What about the displaced people in your plan? what happens to them? It looks to me like the city is trying to strike the best balance it can by moving residents out of the 100-year flood plain, and then protecting and restoring the remainder of the neighborhoods. There’s a lot more green space being created than was there before.

Travis–You’re right the Cedar Rapids plan includes a modicum of new riverfront green space, but mostly the plan is a lesson in denial, fueled by the assumption of massive federal funding. Can any of the victims really return to the lives they had before, after losing everything? Is it really safe to invite them to rebuild in the same location? I don’t put much faith in the earthen berms, removable levee systems and inflatable dams in the plan that will supposedly protect the city from the next ”big one.” That’s the kind of snake oil pedaled by no-money-down ARM brokers who plan to be long gone when the inevitable flood occurs. To a geologist a 500-year flood is tomorrow, not the inconceivably distant future. Besides, with the modern changes in land-use and the global climate we can throw historic 1/500 year flood probabilities out the window. The paper recently published a story saying the flood was predicted just 41 years ago.

see http://www.gazetteonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20081023/NEWS/710239960/1001/NEWS

That’s why I say settle people in new locations and train them for new jobs in an exciting new sustainable venture for the community.

It’s always nice to see some creative thinking coming from our State leaders. Here’s a guest editorial from the Des Moines Register by State Senators Rob Hogg and Joe Bolkcom calling for Cedar Rapids to rethink its plans and preserve the flood plain/river corridor. It includes email addresses for you to voice your support. http://www.robhogg.org/content.asp?ID=1932&I=7332

Hi!

I just came across your blog while doing some research on giant sloths for a novel and I wanted to drop a note to say that this is a fantastic idea. Whether it’s the palaeontology geek or Museum and Heritage Studies student in me saying it, the idea of such a park is wonderful.