How big is our adult sloth? Greg McDonald says the average adult Megalonyx weighed 2,400 pounds (McDonald, 2005). That’s based on a standard formula used to approximate the weight of mammals based on measurements of their femurs, and engineering principles relating the strength of a column to its cross-sectional area. I’m a little dubious about applying the formula to sloths though. There’s nothing normal about the shape of most of their bones. Even a simple measurement like the femur’s diameter isn’t straightforward. Add a lingering uncertainty about sloth locomotion and lifestyle (bipedal vs. quadrupedal), and any weight estimate has to taken with a grain of salt. But, as Greg once told me, you have to start somewhere, and why not with the bone used in all the other mammals, and a bone that’s been recovered often enough to provide a reasonably-sized sample. If you stick to femurs, at least you can compare sloth weights in relative terms. We’ve recovered an adult femur and you’ll see a weight estimate when Meghann, our resident anatomy expert, is sure we’re measuring it from the right anatomical points.

How big is our adult sloth? Greg McDonald says the average adult Megalonyx weighed 2,400 pounds (McDonald, 2005). That’s based on a standard formula used to approximate the weight of mammals based on measurements of their femurs, and engineering principles relating the strength of a column to its cross-sectional area. I’m a little dubious about applying the formula to sloths though. There’s nothing normal about the shape of most of their bones. Even a simple measurement like the femur’s diameter isn’t straightforward. Add a lingering uncertainty about sloth locomotion and lifestyle (bipedal vs. quadrupedal), and any weight estimate has to taken with a grain of salt. But, as Greg once told me, you have to start somewhere, and why not with the bone used in all the other mammals, and a bone that’s been recovered often enough to provide a reasonably-sized sample. If you stick to femurs, at least you can compare sloth weights in relative terms. We’ve recovered an adult femur and you’ll see a weight estimate when Meghann, our resident anatomy expert, is sure we’re measuring it from the right anatomical points.

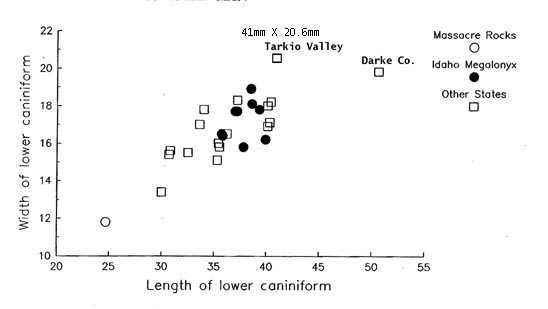

Caniniform teeth, because they are found in fair frequency, offer another way to compare Megalonyx sizes in relative terms. Caniniforms are the front teeth, or tusks, in Megalonyx and some other sloths. Why not just call it a canine? Sloths seem to have evolved them independently from the other mammals in a nice example of convergent evolution, so paleontologists call them a form of canine rather than a canine proper. In the same way, they refer to sloth molars as “molariforms.”

The figure above, taken from McDonald (1998) compares Megalonyx lower caniniforms from 25 different individuals. We added a point showing the approximate measurements of the Tarkio Valley adult. Ground sloths were evolving to grow larger over time, so the size of the tooth suggests we have a late Pleistocene specimen that weighed well over 2,400 pounds–in fact, it may be the second-largest Megalonyx ever found. That will have to do until we get Meghann’s analysis. The point off on the far right is the giant specimen from Darke County, OH that Greg once called the “Arnold Schwarzenegger” of Megalonyxes. Arnold looks to be slightly bigger but we’re not through measuring. All I can say is, “Hasta la vista, baby. . . .” Dave

References

McDonald, H.G. 1998. The Massacre Rocks local fauna from the Pleistocene of southeastern Idaho. WA Akersten, HG McDonald, DJ Meldrum and MET Flints (eds.), In And Whereas. . . Papers on the Vertebrate Paleontology of Idaho Honoring John A. White, Vol. 1, Idaho Museum of Natural History Occasional Paper 36: 156-172.

McDonald, HG. 2005. Paleoecology of extinct Xenarthrans and the great American biotic interchange. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45: 313-333.

Dave, how does the Tariko sloth compare in size with the “Rusty” sloth in the museum?

Good question Pete. Impossible to answer by looking at the teeth unfortunately. “Rusty,” for those who haven’t visited the museum, is modeled on the most complete Megalonyx skeleton known–discovered in the cliffs overlooking the American Falls Reservoir, Power County, Idaho in 1972. The specimen is complete from the first sacral vertebrae forward. It is recorded as #23034 in the Idaho State University Museum.

McDonald (1977) has identified two different forms of jaws and caniniforms in Megalonyx–individuals with small caniniform teeth and a large diastema, or gap, between the caniniform and first molar, and individuals with larger caniniforms, essentially growing into the diastema, leaving a smaller gap. Greg’s theory is this is sexual dimorphism and the sloths with the larger caniniforms are male–possible displaying their choppers to impress the females and intimidate competitors.

By Greg’s theory, #23034 and hence “Rusty” are female; the Tarkio adult is a male, so we can’t simply say the Tarkio caniniform is 14% longer so the animal was 14% larger. We’re going to have to use a different bone to compare–femurs probably, like Greg says. Sounds like another calculation for Meghann. . . .

Greg has recently been doing some thinking about sexual dimorphism in sloths and published a paper about the possible ecological meaning in Harlan’s ground sloth (McDonald, 2006). He admits males are generally the more robust forms in mammals, but there are solid reasons for evolution to take a species in the opposite direction–large newborns, for example, so he could have the theory backwards. It’s a terrific paper.

References

McDonald, HG. 1977. Description of the osteology of the extinct gravigrade edentate Megalonyx with observations on its ontology, phylogeny and functional anatomy. Masters Thesis. University of Florida.

McDonald HG. 2006. Sexual dimorphism in the skull of Harlan’s ground sloth, Contributions ion Science, Natural history Museum of Los Angeles County 510: 1-9.