“This is one of the best examples of a spring marsh I have yet seen. . . ” wrote State Geologist Charles White about this Marion, Iowa fen in the course of his critical statewide survey of Iowa’s wetlands in the fall of 1867 (White, 1867). However, White didn’t come to admire the flora. The future of the State rested upon what he could learn here about turning this peatland into an urgently needed fuel source.

“This is one of the best examples of a spring marsh I have yet seen. . . ” wrote State Geologist Charles White about this Marion, Iowa fen in the course of his critical statewide survey of Iowa’s wetlands in the fall of 1867 (White, 1867). However, White didn’t come to admire the flora. The future of the State rested upon what he could learn here about turning this peatland into an urgently needed fuel source.

Coming largely from the forested eastern U.S., Iowa’s early settlers were the first to encounter vast expanses of prairie, and face the bleak prospect of developing an economy without a ready supply of wood. The soil was incomparable and opportunities boundless–limited only the fuel shortage. Timber was in desperately short supply, especially in the north and west, and disappearing rapidly everywhere. Once it became evident Iowa’s coal deposits were limited to the southern counties, hopes coalesced around peat as a source of energy. . . at least as a stopgap until new forests could be grown. White wrote (1868):

Our peat “. . . will soon become invaluable. . . for (it) lies wholly beyond the limits of the coal-field, and the timber, although enough for the present inhabitants, can not supply a tithe of the fuel which the prospective population of a region so fertile and inviting, will soon demand. Peat has there a local value which can not be questioned.”

Our peat “. . . will soon become invaluable. . . for (it) lies wholly beyond the limits of the coal-field, and the timber, although enough for the present inhabitants, can not supply a tithe of the fuel which the prospective population of a region so fertile and inviting, will soon demand. Peat has there a local value which can not be questioned.”

Mention peat today, and potting soil or fertilizer probably springs to mind—not so for earlier generations. Dwindling timber supplies had stirred some limited commercial fuel ventures in New England early in the century (Hawes, 1912), but few native-born Americans had any direct experience with burning peat. Cultural roots and memories run deep though, and many Iowa families were of northern European stock, with a long tradition of burning peat. Some British and Irish immigrants, coming here to farm or build railroads, found themselves overseeing peat operations instead (Cedar Falls Gazette, 1867).

Half the peat harvested in the world today is used for fuel (Turetsky and St. Louis, 2006). The European Union has 125 peat-fired power plants, mostly in Finland and Estonia, with more being announced every year (International Peat Society, 2010). Some of the new plants are 100% peat-fired, but many older coal-fired plants are converting to co-burn peat, reducing their average mercury and sulfur emissions and significantly extending their service lives.

Half the peat harvested in the world today is used for fuel (Turetsky and St. Louis, 2006). The European Union has 125 peat-fired power plants, mostly in Finland and Estonia, with more being announced every year (International Peat Society, 2010). Some of the new plants are 100% peat-fired, but many older coal-fired plants are converting to co-burn peat, reducing their average mercury and sulfur emissions and significantly extending their service lives.

Good dry peat is a light clean fuel. It is easily kindled and burns with a hot red flame leaving little smoke, soot or ash. Unlike coal, though, there is no clinker or slag; low sulfur means no acid rain either. There’s a pungent odor to burning peat that some people find objectionable, but others liken to Scotch whisky. Pound for pound, plain dry peat has about the same heating value as pine (Savage, 1905), but owing to its lower density, needs twice the storage space—8-18X more than coal (Davis, 1907).

Peat is the partially decayed remains of plants. It is the permanent saturation by water keeping dissolved oxygen low that retards decomposition and distinguishes a peat-bog or fen from a marsh (which dries out occasionally, speeding decomposition). The types of plants, the degree of decay and chemical composition of peat vary widely. It may be a light and fibrous sponge, or a dense black muck with no visible structure–changing by depth and location in the bed. The usual sequence of a deposit is a tough fibrous mat overlaying a progressively denser and darker muck, but depending on the hydrology of the site, this sequence can be reversed, or repeated, with sediment inter-layered. Given enough time, heat and pressure, a deposit of peat will be transformed into a more uniform bed of coal, but at this stage it’s a highly variable natural living raw material.

Peat is the partially decayed remains of plants. It is the permanent saturation by water keeping dissolved oxygen low that retards decomposition and distinguishes a peat-bog or fen from a marsh (which dries out occasionally, speeding decomposition). The types of plants, the degree of decay and chemical composition of peat vary widely. It may be a light and fibrous sponge, or a dense black muck with no visible structure–changing by depth and location in the bed. The usual sequence of a deposit is a tough fibrous mat overlaying a progressively denser and darker muck, but depending on the hydrology of the site, this sequence can be reversed, or repeated, with sediment inter-layered. Given enough time, heat and pressure, a deposit of peat will be transformed into a more uniform bed of coal, but at this stage it’s a highly variable natural living raw material.

Peat is more than just a sodden compost heap of leaves and stems. The aerated top layer of a peat bed is interwoven with the roots and rhizomes of living plants. Most store their food and overwinter here. Nutriments like this made wetlands an attractive destination for hunter-gatherers, especially in the spring after a hungry winter, before the uplands had much to offer. Native Americans had the tools needed to access this underground bounty–few animals do, however, except for moose  maybe. . . and ground sloths. More than a few of the Megalonyx skeletons found in situ, including our Tarkio trio, have been recovered from bottomlands—three of the more complete specifically from peat bogs like this one (McDonald, 1998).

maybe. . . and ground sloths. More than a few of the Megalonyx skeletons found in situ, including our Tarkio trio, have been recovered from bottomlands—three of the more complete specifically from peat bogs like this one (McDonald, 1998).

Still, peatlands are relatively barren of wildlife compared to other ecosystems. The living conditions that make life hard for plants, affect animals too (e.g. high water, low oxygen (for the burrowers), etc. ). Small mammals stick to the hummocks and the trails left by deer and other visitors. Travel is difficult, unless you’re a bird, and dangerous besides, judging from the many bison bines uncovered here and elsewhere (Toennies, 2003). Generally, visitors find what they need, and leave. It may not be food or water drawing sloths and bison here though–some of these plants may offer trace elements the animals need. Caribou retreat to boreal bogs for calving to avoid wolves (Rettie and Messier, 2000) . . . our “baby” is older than that though.

Sphagnum and Hypnum mosses make up the bulk of boreal peat-bog deposits but sedges predominate in Iowa’s beds (Pammel, 1909). Trees and shrubs are an important component of some northern bogs but they were less common here–only likely to invade after drainage and intense grazing or other disturbance (Middleton, 2002). From an energy perspective, the specific plants that make up peat are less important than the impurities. Contamination like loess, silt and sand, the shells of mollusks, and the bones of the occasional mammal that falls in, are unburnable and leave ash—too much (>25%) and the peat is worthless as a fuel.

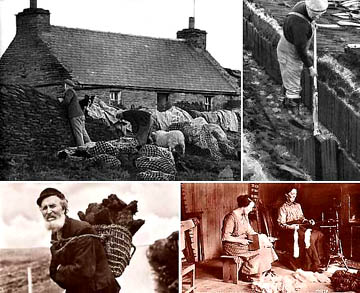

In Europe, peat was traditionally harvested by hand—cut into blocks or turves with special peat-spades (“slanes” in Ireland) and then air-dried. Working together, an average family could cut enough peat in one week to heat a cottage all winter (Rotherham, 1999). Cutting and lifting the heavy wet sod was work grown-ups; children usually saw to drying the blocks—carefully turning and restacking them several times over four to six weeks to expose fresh surfaces to the sun and wind. The blocks are highly friable and break apart easily with rough handling. Drying had to be finished by winter—ice crystals destroy the structure, and frozen wet blocks collapse upon thawing. An average household needed 5-8,000 turves per year—a stack that could be as large as the house itself (ibid.).

In Europe, peat was traditionally harvested by hand—cut into blocks or turves with special peat-spades (“slanes” in Ireland) and then air-dried. Working together, an average family could cut enough peat in one week to heat a cottage all winter (Rotherham, 1999). Cutting and lifting the heavy wet sod was work grown-ups; children usually saw to drying the blocks—carefully turning and restacking them several times over four to six weeks to expose fresh surfaces to the sun and wind. The blocks are highly friable and break apart easily with rough handling. Drying had to be finished by winter—ice crystals destroy the structure, and frozen wet blocks collapse upon thawing. An average household needed 5-8,000 turves per year—a stack that could be as large as the house itself (ibid.).

Preparing peat for fuel was a demanding process–one traditional peoples in Europe had managed for at least two thousand years (Rotherham, 2009), but in the U.S., where labor costs were high, exploiting peat for a mass market faced some daunting challenges. Nonetheless, a far-thinking group of Quakers came here to Marion, Iowa in 1866 to tackle the challenge, and put the State, and perhaps the Nation, on the path to energy independence. Next time: The Marion peat enterprise. . . . Dave

References

Cedar Falls Gazette, February 8, 1867.

Davis, C. A. 1907. Peat: essays on its origin, uses and distribution in Michigan. State Board of Geological Survey. Lansing, MI.

Hawes, J. W. 1912. An Historical Address: Celebration of the 200th anniversary of the incorporation of Chatham, Mass. C. W. Swift, Publ. Where?

Huels, F. W. 1915. The peat resources of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey.

McDonald, H. G. 1998. The sloth, the president, and the airport. Washington Geology 26: 40-42.

Middleton, B. 2002. Nonequilibrium dynamics of sedge meadows grazed by cattle in southern Wisconsin. Plant Ecology 161 89-110.

Pammel, L. H. 1909. Flora of northern Iowa peat bogs. Iowa Geological Survey 19: 739-784.Rettie, W. J. and Messier F. 2000. Hierarchical habitat selection by woodland caribou: its relationship to limiting factors. Ecography 23:466–478.

Rotherham, I. D. 1999. Peat cutters and their landscapes: fundamental change in a fragile environment. Landscape Archaeology and Ecology 4: 28-51

Rotherham, I. D. 2009. Peat and Peat Cutting. Shire Publications, Oxford, England

Savage, T. E. 1905. 2 A Preliminary Report of the Peat Resources of Iowa. Iowa Geological Survey Bulletin No 2. Des Moines, IA

Toennies, J. L. 2003. Dows Holocene fossil bison assemblage, Franklin County, Iowa: Its application to conservation, interpretation, and outreach. University of Iowa, Department of Geoscience, M. Science thesis.

Turetsky, M. and St. Louis, V. L. 2006. Disturbance in boreal peatlands. In Ecological Studies, Vol. 188, Boreal Peatland Ecosystems. R. K. Wieder and D. H. Vitt (Eds.), Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg.

White, C. A. 1867. Marion Register, December 11, 1867.

White, C. A. 1868. First and Second Annual Report of the State Geologist. F. W. Palmer, State Printer. Des Moines, Iowa.